From Banter to Menace, Hangmen Poses Questions on Violence

Without being didactic, Hangmen pushes us to think and reflect on state violence, death punishment, justice, and the restraint and humility required in law enforcement.

By Mingsi Ma

I almost feel a little dizzy at the Pittsburgh premiere of playwright Martin McDonagh’s Hangmen by Kinetic Theatre Company at Carnegie Stage; with the seating’s proximity to the stage, I feel like slipping into an anachronism, a crack in the physical space, as if I am traveling back in time. The story is set in 1965, a time when the death penalty has just been abolished in the U.K. The lens of McDonagh’s story narrows in on Harry Wade, played by Simon Bradbury. This second-best hangman in the country now runs a small pub with a lot of frequenters. Curious journalists and nosey locals crowd inside his pub to learn about what he has to say about the abolition and hear the “tea” – all till the arrival of the mysterious young man Monney, turning the day from banter to menace.

Throughout the night, the sound of “Ya,” “Aye,” and “Lad,” the H-dropping, and the somewhat melodic way of speaking from Northern England splash against my ears. Dialect coach Brandi Welle is phenomenal at training this team of actors onstage to transport us to this dim pub in Oldham, Greater Manchester.

I find myself loving the lighting design when Mooney, played by Charlie Kennedy, and Syd, played by James Fitzgerald, sit in a diner on a rainy night. Transitioning from the intermission, I absolutely adore how lighting designer Andrew David Ostrowski and scenic designer Johnmichael Bohach start the scene. They draw the audience’s attention back to the stage by darkening the room, blinking twice the open sign at the back, and then having the overhead light fall on the food on the table while casting some shadow on the two characters’ faces to add depth to the storytelling. The vintage red dining table, the dark but slightly blue backdrop, and the beam remind me of Nighthawks by Edward Hopper.

Charlie Kennedy’s portrayal of Mooney left a strong impression on me. In Hangmen, Mooney disrupts the peace in the pub, flirts with the hangman’s daughter, challenges the hypocrisy around the death penalty, and evokes theatrical conflicts. I find this character the most nuanced and unpredictable of them all: with unclear intentions and an untold backstory, he comes across as erratic, unsettling, somewhat creepy, and, in his own word, “menacing.”

Although Kennedy is one of the youngest cast members and is said to have Mooney as his first professional role after recently graduating from Point Park University, his early-career performance, with a hint of deliberate theatricality and a little stiffness, suits the character remarkably well. The smile that never reaches his eyes, the glint of balefulness when he looks around, the slight hunch of his neck, and his inopportune remarks all contribute to Kennedy’s compelling and memorable interpretation.

Hangmen is an absurd black comedy. If people are looking for a cohesive, mystery-solving drama, this is probably not the one. Why does Mooney show up at Harry’s pub and hide the whereabouts of his daughter? Is Hennessy falsely executed? Why do the pub’s regulars say nothing about Harry and his crime? Does Harry eventually face any repercussions for the crime he committed? So many questions left unanswered. Still, McDonagh’s satire is everywhere. Without being didactic, Hangmen pushes us to think and reflect on state violence, death punishment, justice, and the restraint and humility required in law enforcement.

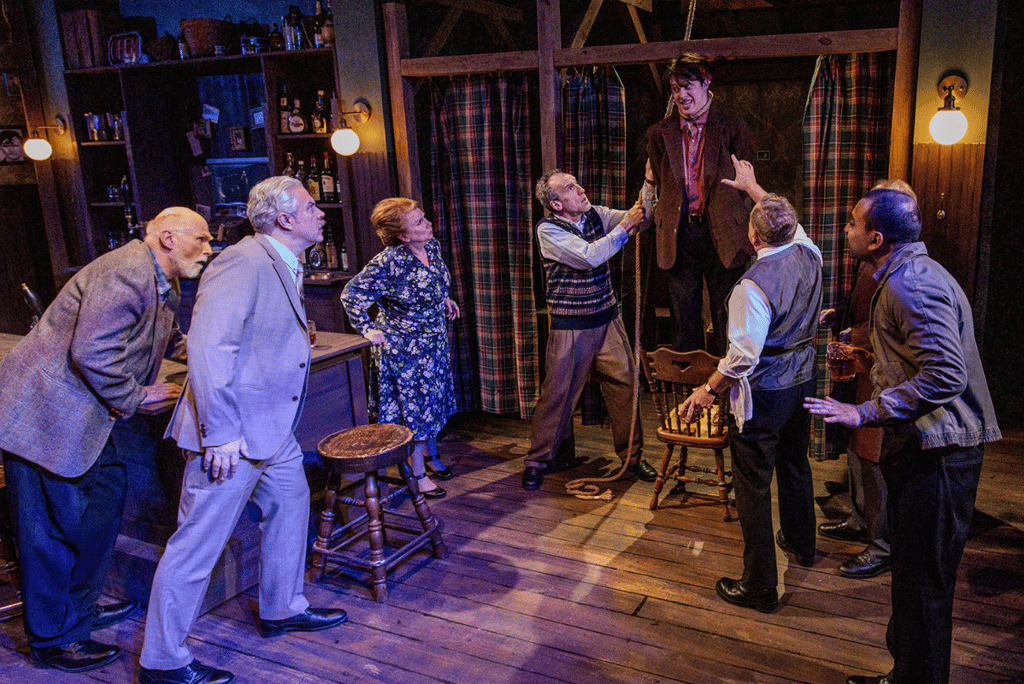

From left to right: John Reilly, Simon Bradbury, Arjun Kumar. Photo Credit: Rocky Raco

The hangman Harry is given the power to place himself above the lives of the criminals he executes, serving as an agent of state violence. This violence is justified as a means of preserving and enforcing the law. Harry keeps telling the journalist, “I’ve been a servant of the Crown in the capacity of hangman,” and insists on “[keeping his] own counsel.” The sense of authority is even further extended by him to his personal life when he speaks to his family in a demanding tone, or when he competes with another hangman over the number of people they have executed. His apathy and dissociation during law enforcement are alarming and disturbing.

At the end of Hangmen, McDonagh adds a brilliant plot twist by having Harry commit a horrendous crime and exposing the character’s indifference to violence. Why is everyone at the pub so calm at the end of the show, even after witnessing the crime? Is McDonagh using these quiet bystanders as a metaphor? The performance leaves us with no resolution, yet more to reflect on after the play.